Introduction: From Waste Fragments to Global Threats

A plastic bag used for just a few minutes may drift in the ocean for centuries, becoming microplastic fragments in fish, seeping through the salt we consume, and returning to our bodies. Marine plastic waste is therefore not merely an environmental problem, but a contamination cycle that connects to everyone’s lives. This article invites exploration of plastic’s journey, from waste management on land to garbage patches in the middle of the ocean, tracking the hidden impacts on marine life and the economy beneath the waves, and considering response approaches that begin at the source, not the endpoint.

Chapter 1: How Plastic Travels from Our Hands to the Sea

Every day, plastic waste from people around the world flows into the ocean through small behaviors we overlook, such as improper waste disposal and inadequate waste management from roadside bins in major cities to small communities without proper waste disposal systems. The amount of plastic humans use continues to increase without stopping, and failed waste management in many areas is driving this crisis to become more severe. Every year, humans produce more than 400 million metric tons[1] of plastic, equivalent to the combined weight of all humans on Earth. Some of this plastic consists of packaging used for just a few minutes but remains in nature for hundreds of years, and along the way may break down into microplastics that leak into the bodies of other living organisms.

Although less than 0.5% of produced plastic is improperly disposed of and escapes into the ocean, this figure means that more than 1 million metric tons of plastic still flow into the sea every year, enough to form massive floating garbage islands and destroy marine ecosystems in the long term. This is therefore not merely a problem of the sea but a global crisis that directly undermines our environment, economy, and health.

[1] Metric ton is a unit of mass measurement in the metric system, equal to 1,000 kilograms.

- The Role of Rivers and Coastal Cities in Carrying Plastic to the Sea

The journey of plastic waste from human hands to the sea does not occur by chance. It is the result of waste management infrastructure and resource use behaviors that vary greatly between regions worldwide. Only 9% of plastic worldwide is recycled, while another approximately 22% becomes uncollected waste or remains in the environment without proper management.

High-income countries may appear to be the world’s main plastic users, and this is indeed true, but waste management systems in these countries are typically highly efficient, preventing the massive amounts of plastic used from escaping into nature. Conversely, low-income countries, despite using less plastic, still have unavoidable gaps for plastic pollution due to lack of waste disposal systems. However, the most concerning sources of pollution are actually middle-income countries, where plastic use is expanding rapidly, but waste management infrastructure has not kept pace with increasing consumption. This imbalance has become the most vulnerable point in the global contamination cycle.

Under normal weather conditions, rivers function as waterways, but when heavy rain falls, plastic on roads or along canals is swept into rivers in significantly larger quantities. Rain events can increase plastic discharge by up to 10 times within just a few hours. Rivers thus become major arteries carrying plastic from land to sea. However, not every piece of plastic floating in rivers reaches the ocean. Much plastic sinks along the way or gets trapped along riverbanks and riverbeds. Nevertheless, the closer plastic is to rivers, and the closer those rivers are to the sea, the higher the chance of reaching the ocean. It has been identified that just 1,000 rivers worldwide are the source of nearly 80% of plastic discharge flowing into the ocean.

- Marine plastic waste does not originate from the sea but begins on land

Plastic is a material humans created to facilitate daily life. Each year, the world produces more than 300 million tons of plastic, with half being single-use products such as cups and straws. Without proper management systems, at least 14 million tons of plastic enter the ocean. This figure may seem small compared to total production, but its impact is enormous. Plastic fragments, which have become a familiar sight in the ocean, account for approximately 80% of all marine debris, found from the water surface and beaches to coral reefs, especially in tourist areas and densely populated zones.

Although plastic is found floating in the middle of the ocean, the main source of marine plastic actually comes from land, whether from urban drainage systems, household wastewater, or industrial activities, where improperly disposed waste is often washed by rainwater into canals and rivers before flowing to the sea. Additionally, plastic pollution from marine activities such as fishing, water transportation, and aquaculture is another important mechanism for feeding waste into marine ecosystems.

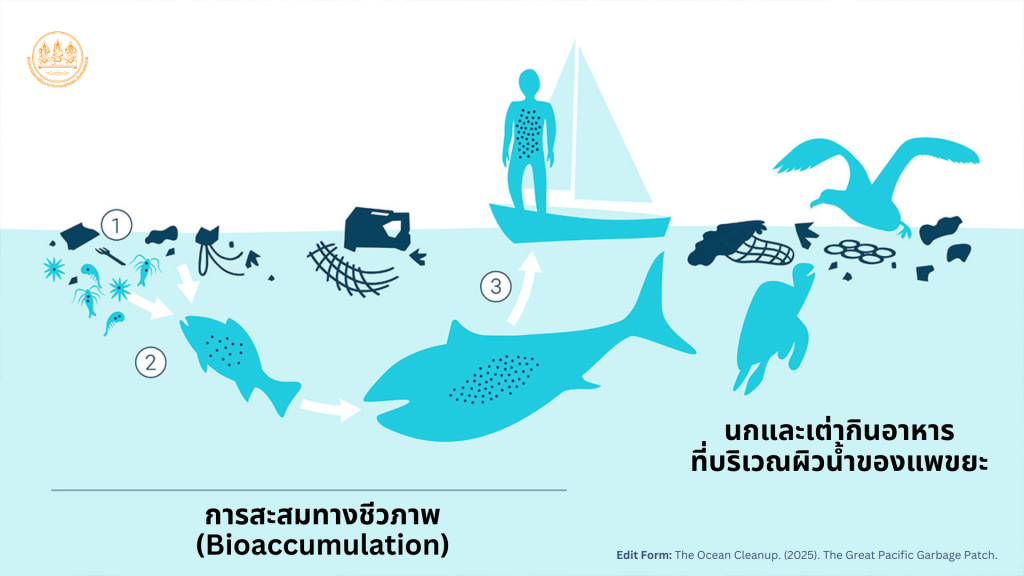

When these plastics enter the environment, whether on land or in the sea, transformation processes gradually begin. Amid sunlight, wind, and waves, plastic does not decompose but breaks down into small fragments called microplastics (smaller than 5 millimeters) or eventually becomes nanoplastics (smaller than 100 nanometers). This microscopic size allows marine life to ingest them unknowingly, marking the beginning of contamination that is difficult to reverse.

- Mechanisms of Plastic Waste Accumulation in Ocean Currents: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

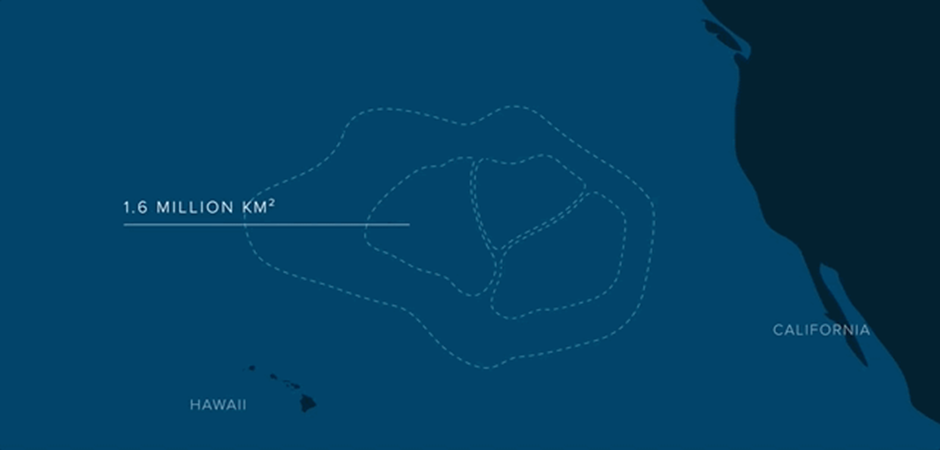

In the middle of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and California, there is an area that does not appear on tourist maps but has become a massive center for plastic waste accumulation. This is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Since most plastics have lower density than water, they float on the surface and are swept into the center of rotating ocean currents that circulate and carry plastic from around the world to accumulate and form large garbage patches.

Research by The Ocean Cleanup found that this garbage patch covers an area of approximately 1.6 million square kilometers, equivalent to three times the area of France. This data comes from sampling by 30 ships, 652 net points, and aerial surveys, showing an overview of floating debris. Within the garbage patch, there are more than 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic, weighing approximately 100,000 tons, equivalent to more than 740 Boeing 777 aircraft. This figure is 4 to 16 times higher than previously estimated, with the central area having the highest debris density. This phenomenon is not a natural coincidence but the result of human waste management failure, permanently transforming the ocean into a plastic refuge.

After plastic leaks into the sea, the distribution process does not occur randomly. Research found that approximately 80% of floating plastic is washed back to shore within one month, while another amount of plastic may sink to the seabed immediately, especially low-density plastics that absorb water quickly. PET bottles[2], when filled with water, sink easily, while bottle caps that are lighter and more resistant to sinking tend to float longer and travel farther than other types.

[2] PET bottles are plastic bottles made from Polyethylene Terephthalate material, lightweight, tough, durable, flexible against impact, transparent, intended for single use but can be reused and easily recycled.

Source: The Ocean Cleanup (2025)

Chapter 2: Plastic in the Ocean and Multi-dimensional Spreading Impacts

Plastic accumulated in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch gradually breaks down into smaller microplastics from sunlight, wind, and waves. Microplastics have become a global problem affecting marine ecosystems, marine animal health, and the quality of seafood consumed by humans. They also impact human health, coastal tourism economies, and contribute to accelerating climate change.

- Impact of Plastic on Marine Animals and Marine Ecosystems

The impact of plastic on marine animals is clearly evident in every dimension of the food chain. Plastic fragments in the sea are mistaken for food by various animals, including seabirds, seals, fish, and sea turtles. Ingesting plastic makes these animals feel full without nutrition, leading to starvation, choking, or internal injuries, while also losing swimming ability or risking infection.

In the Pacific garbage patch area floating on the water surface, plastic outnumbers marine life by 180 times, resulting in animals that inhabit or migrate through such areas having a high tendency to ingest plastic. In some cases, when analyzing what is in sea turtle stomachs, plastic was found in up to 74% of stomachs.

Additionally, abandoned fishing nets, or ghost nets, account for 46% of the total mass in this garbage patch. Marine life that swims or moves through these nets tends to become entangled, unable to escape, and often dies eventually. Plastic entanglement is thus another form of death hidden in the ocean.

- Spread of Microplastics and Impact on Human Health

Microplastics have been detected in tap water, salt, and oceans everywhere, including in human placentas. Although further research is needed to assess prevalence, this discovery demonstrates the level of widespread contamination. Moreover, chemicals used in producing certain types of plastic are carcinogenic and endocrine disruptors, which may impact development, reproductive systems, nervous systems, and immunity in both humans and animals.

Additionally, plastic absorbs toxins from seawater, and when animals ingest plastic, these toxins accumulate in the digestive system and circulate further in the food chain. The transfer of toxins from marine animals to humans is therefore a risk under ongoing study.

- Economic Impact of Marine Plastic

Microplastics create economic impacts on the global economy valued at 6-19 billion US dollars per year, covering impacts on tourism, fishing, aquaculture, and cleanup costs. Tourist destinations filled with plastic naturally reduce attractiveness, affecting national income and people’s quality of life. Additionally, plastic creates hidden health and ecosystem costs that cannot yet be fully assessed. Therefore, managing plastic waste from the source is much more effective than dealing with impacts that have already occurred in the sea.

- Plastic and Accelerating Climate Change

Plastic does not just destroy the ocean but has an important role in climate change. When plastic is burned, it releases carbon dioxide and methane from landfills into the atmosphere, increasing pollution levels and accelerating greenhouse reactions.

Source: The Ocean Cleanup (2025)

Chapter 3: Solving Marine Waste Must Start from the Source, Not Just the Endpoint

Fighting marine waste is no longer a mission that can rely solely on downstream management measures, but must begin at the source of the problem, namely production processes and consumption behaviors that result in marine waste continuing to increase. Despite years of efforts to reduce marine waste, ocean restoration still cannot keep pace with consumption rates.

At the global level, the United Nations has established the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development), particularly Goal 14 on conserving and sustainably using oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development, which clearly states in sub-target 14.1 to significantly prevent and reduce marine pollution, especially pollution from land-based activities, including plastic waste and excess nutrients that escape into the sea.

However, global goals cannot be achieved without regional cooperation. A clear example is the Bangkok Declaration on Combating Marine Debris in ASEAN Region (Bangkok Declaration on Combating Marine Debris in ASEAN Region), which was endorsed at the ASEAN Special Ministerial Meeting on Marine Debris in 2019, emphasizing cooperation to protect coastal and marine environments, support research, innovation, and participation of all sectors to create sustainable mechanisms for dealing with rapidly increasing plastic waste.

Meanwhile, the ASEAN Framework of Action on Marine Debris, which was endorsed at the ASEAN Summit in 2020, is another important driving force. This framework aims to promote development of regional action plans, academic and innovation support for driving behavioral change, and systematic private sector participation, emphasizing support for scientific and technological knowledge to lay foundations for long-term policies in effective marine waste management.

The statement by Dato Lim Jock Hoi, former ASEAN Secretary-General, clearly emphasizes the overall picture of this problem:

Image source: UN Women (2021)

Although Thailand has improved its ranking from being the 6th largest plastic waste discharger into the sea globally in 2015 to 10th place in 2021, it still faces ongoing challenges in managing this problem. To seriously elevate operations, Thailand has therefore developed the Plastic Waste Management Action Plan Phase 2 (2023-2027), which has a comprehensive structure from upstream to downstream, divided into 4 main measures: Measure 1 – Production of environmentally friendly plastic products, Measure 2 – Reduction of plastic waste in consumption stages, Measure 3 – Post-consumption plastic waste management, and Measure 4 – Marine plastic waste management.

This plan is driven into actual practice through clear mechanisms, including campaigns, creating shared understanding in society, establishing specialized working groups, as well as budget allocation and international cooperation through financial instruments and international support projects, to make plastic waste management efficient and sustainable.

One concrete innovation example is the SCG – DMCR Litter Trap, a floating waste trap buoy developed jointly between the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources and SCG Chemicals Public Company Limited (SCGC). This buoy can support waste weight up to 700 kilograms per unit and has a service life of over 25 years, made from special grade HDPE material that is fully recyclable. Currently installed in 17 provinces and has been able to reduce marine waste by over 90 tons since 2020.

Mr. Pinsak Suraswadi, Director-General of the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources, stated:

Image source: ThaiHealth. (2024)

Looking at the overall picture, it can be seen that marine waste management cannot wait for only downstream measures such as collecting waste in the sea or on beaches, but requires structural reform from the source to comprehensively cover production, consumption, public awareness creation, and systematic coordination of both domestic and international cooperation. Importantly, all measures will be meaningless without driving force from all sectors of society.

Conclusion: Marine Plastic Waste Is No Longer a Distant Issue

The marine plastic waste problem clearly reflects the connection between our small behaviors and impacts that expand to the macro level. Plastic waste does not start from the ocean and should not end in the ocean, because every piece of waste that escapes management has the opportunity to infiltrate the fish on our plates, the salt on our dining tables, and our daily consumption.

Although today there is abundant data, research, and case studies to support action, the lack of strong mechanisms and serious cooperation remains a significant obstacle to turning the situation around. The ocean cannot wait for slow change any longer. Addressing this crisis requires starting from policy structures, management systems, and overall social attitudes, not just cloth bags in consumers’ hands.

Strategy and International Cooperation Coordination Division

Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council

References

IUCN. (2024). Marine Plastic Pollution: Issues Brief. Retrieved from https://iucn.org/sites/default

/files/2024-04/marine-plastic-pollution-issues-brief_nov21-april-2024-small-update_0.pdf

MATH.net. (n.d.). Metric ton. Retrieved from https://www.math.net/metric-ton

NBT CONNEXT. (2025). Ministry of Natural Resources elevates marine waste management-ecosystem restoration, assigns DMCR to cooperate with network partners to manage marine waste problems with new innovation “SCGC – DMCR Litter Trap Gen 3″ waste trap buoy. Retrieved from https://thainews.prd.go.th/thainews/news/view/876572/?bid=1

Recycle Day Thailand. (2019). What are PET bottles? Retrieved from https://shorturl.asia/a8duF

The Ocean Cleanup. (2024). Ocean plastic pollution explained. Retrieved from https://theoceancleanup.com/ocean-plastic-pollution-explained/

The Ocean Cleanup. (2025). The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Retrieved from https://theoceancleanup.com/great-pacific-garbage-patch/

UN Women Asia and the Pacific. (2021). Message from H.E. Dato Lim Jock Hoi, Secretary-General of ASEAN, highlighting ASEAN’s commitment to advance Women, Peace and Security agenda. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KwGvfOyNqgg

World Bank. (2021). ASEAN Member States Adopt Regional Action Plan to Tackle Plastic Pollution. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/05/28/asean-member-states-adopt-regional-action-plan-to-tackle-plastic-pollution

Pollution Control Department. (2023). Plastic Waste Management Action Plan Phase 2 (2023-2027). Retrieved from https://hub.mnre.go.th/th/knowledge/detail/63530

Thai Health Promotion Foundation. (2567). Thailand’s first ThaiHealth unites partner forces “Lanta Island Declaration” to elevate quality tourism destinations, solve marine waste problems and coastal erosion. Retrieved from https://shorturl.asia/Gfa7l